Everyone has a natural genius zone just waiting to be explored. Some learn to channel it early on. Others learn to connect with it much later in life. But I guarantee that this place lies dormant within each of us.

First, how to define our natural genius. This is an ability to do or understand something that you seem to be able to do better than most--that thing which feels very natural. Simply put, this is an ability that seems too easy. This could be as broad as a musical concept, to something as specific as being able to play some crazy sound on your instrument. Whatever the case may be for you, this is a skill or perception in which you own.

The deceptive thing about our natural genius zone is that we are able to create, perform or think from this space with such ease that we can easily perceive it as being too easy. To the point that we feel anything produced from this space has no merit. We've convinced ourselves that unless it takes us several years and countless hours to develop something, it has no value. So instead, we only focus on that which we cannot do--that which appears to be too difficult. Sometimes this is indeed necessary.

Imagine if Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor ignored that which is uniquely them and just focused on what they were not able to do. What if Ornette only focused on playing with the hard bop sophistication of Sonny Rollins and the technical virtuosity of John Coltrane. Or what if Cecil Taylor only strived for the relaxed swing feel of Wynton Kelly or to play with the Romantic introspection of Bill Evans? New schools of improvisation would have never unfolded.

I wonder if abstract painter Jackson Pollack felt similar doubts when he found himself inside his natural genius zone where he basically did all of the things painters are taught not to do: he dropped and spilled paint onto a canvas while it lain on the floor. He flung and hurled paint at canvasses with no discernible logic. As a painter, he had probably seen the type of asymmetrical collage that defined his drip style all around him for most of his life--on his clothes, the floor, his shoes, splattered all over his easel. He probably thought nothing of it. These things were probably discarded as messes--things to be cleaned up after he'd finished painting the conventional way. Fortunately, he had the insight to turn these drips, splatters, and spills into masterpieces.

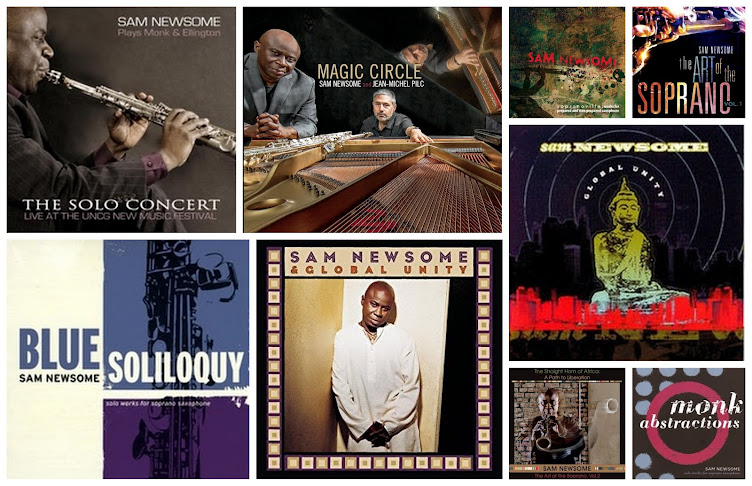

On my new recording, I had a similar creative insight as Pollack when I recorded a few pieces made up of percussive key clicks produce by pressing down the keys on the soprano in a succession so that they created a rhythmic pattern. For most jazz purists, this kind of experimentation would immediately activate ones "bullshit meter." But much to my surprise, it was anything but. As you can imagine, merely pressing down the keys of the saxophone without actually blowing air into it, did actually feel too easy. But it did not make the final result less valid. Quality work has no time preparation prerequisite. Does a meal that takes 15 minutes to prepare taste less delicious than one that takes two hours? Not necessarily.

So the next time you find yourself in your natural genius zone doing something which seems too easy, don't discard it as being unworthy of much deeper exploration. We do not always have to travel uphill on our creative journey. We can get to some nice places traveling with the wind too.